Watch Information and History

[Hamilton] [Bulova] [Accutron] [Water Resistance] [ETA 2824] [ETA 2892]

ETA 2824 – Another Little Engine that Could

ETA 2824 vs Eterna Caliber 1429U

Text and images by A Watchmaker

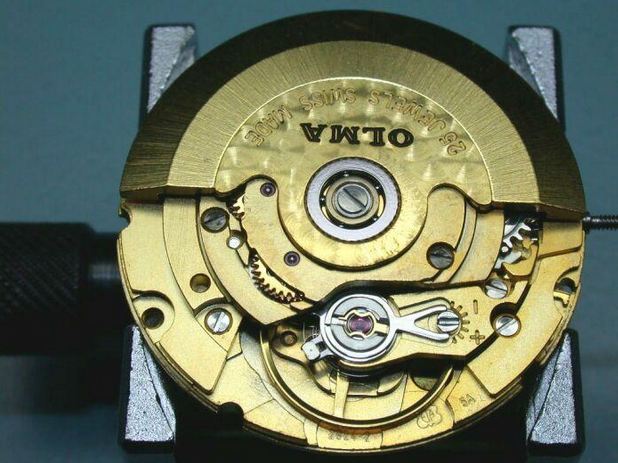

In response to an article on the ETA 2892 written by a befriended watchmaker, many people requested that he took a closer look at that movement’s “smaller brother”, the ETA 2824.

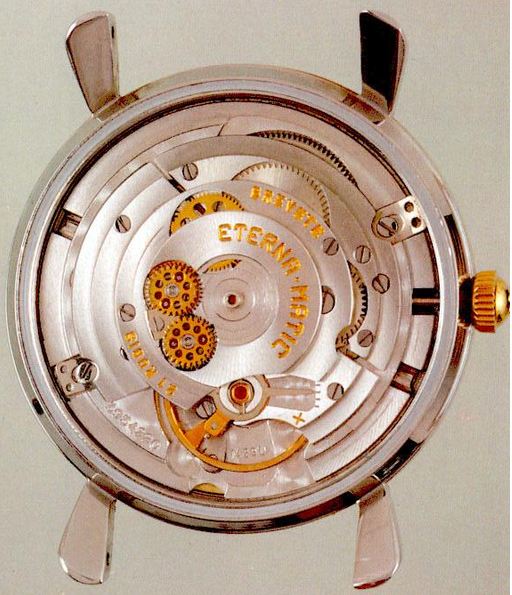

Looking through Heinz Hampel’s excellent book, ‘Automatic Wristwatches from Switzerland’, it appears to me as though the ETA 2824 is also an Eterna derived caliber. Although not identical, it definitely seems that the Eterna Caliber 1429/1439 U was used as the base design for the ETA. I’m no expert in movement design, or movement history, so perhaps one of our technically minded history buffs can make further inquiries in that regard. Like it’s Eterna cousin, the Caliber 1466U, it too started out at a leisurely 18,000 BPH. It does predate the latter by a couple of years though, being introduced in 1961, according to Hampel.

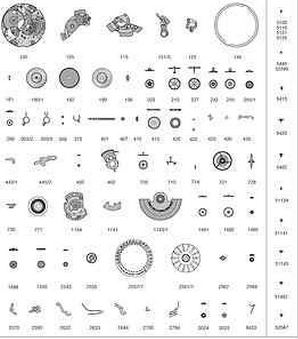

Eterna Caliber 1429U

Like all ETA products it too has undergone continuous refinements to bring us the work horse that we know today. If one were to check through old technical literature, one would see that this caliber has also had many reincarnations in slightly different guises and beats. All the way from 18,000 BPH, right up to the super-fast 36,000 BPH. Often times, many of the parts being completely interchangeable.

Dimensions and Differences

Dimensions are very similar to the 2892. Casing diameter is identical, 25.6mm, but the overall height is slightly more, 4.6mm versus 3.6mm. That doesn’t sound like much, only 1mm thicker. Still, considering the small dimensions that we’re dealing with, 4.6mm is almost 28% thicker than 3.6mm.

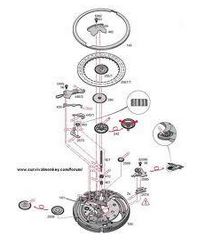

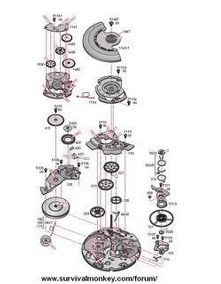

As one can see when comparing pictures of the two movements, they have many similarities. I’m not going to point out every single difference between them, but the main differences are:

- more generously proportioned wheels

- larger diameter balance wheel

- smaller diameter ball bearing race support

- crown and ratchet wheel fit on top of the barrel bridge

- two reversing wheels in the automatic winding system

- the automatic unit fits on top of the movement.

Why Both are so Beloved by Watch Companies

Generally, integrating the automatic unit into the movement and fitting the crown and ratchet wheel underneath the barrel bridge results in a slightly thinner movement. Both of them have a very similar layout of the drive train, namely, the great wheel, third wheel and second wheel (still erroneously referred to as the fourth wheel by many) are almost in a straight line, with the escape wheel slightly offset to the side. Both of them supply the drive to the dial train via the third wheel. Most significantly, both lend themselves well to the attachment of modules and extra complications and both have plenty of torque to spare in order to drive said complications without drastically affecting either the amplitude or the timing.

In fact, if the attachment of any module reduces the balance amplitude by more than 15 to 20 degrees, then that module is obviously in need of a service. This should be a cause of concern for most customers, because the majority of watchmakers do not service these modules. They are removed, the basic movement serviced and then reattached. Most major brands don’t bother servicing them,o either. They just fit a brand new movement and module and return the old one to Switzerland for refurbishing, and the service charge usually reflects this.

Why? Because most of these modules, be they chrono or perpetual calendar modules, are very complicated and require qualified technicians to service and adjust them. Attachment of a module in dire need of a service, or one serviced incorrectly, can pull the amplitude down by as much as 200 degrees. Such a watch, regardless of how stellar the performance of the basic movement is, will not keep good time on the customer’s wrist.

Accuracy

So, the million dollar question that most aficionados have been waiting for – how does the ETA 2824/2 compare to the ETA 2892-A2? Or more specifically, is it as accurate and as reliable as the latter?

Keep in mind that the following is my own personal opinion, and in that area I am influenced only by what I see at the bench and my experience gained from working on these and many hundreds of other movements.

I don’t see any difference in accuracy between the two, provided that they are both fitted with the highest – chronometer – grade parts, carefully lubricated and adjusted to the best accuracy possible. Of course, very few fall into that category, so it’s no wonder that the 2824 has gotten a bad rap as the 2892’s poor cousin.

Reliability

As far as reliability is concerned, they seem to be on a par, but I do think that the 2892 has the edge when it comes to long-term wear, or lack thereof. The larger support for the ball bearing races means better support and hence better shock protection for the oscillating weight. Also, because this has been ETA’s inexpensive work horse for so long, and only recently started supplying it with the highest quality parts, ETA haven’t invested the same amount of effort into refining this movement, as they have in the 2892. This is best seen in the automatic unit, which doesn’t appear to have undergone much change since it’s days as an Eterna incarnation. As a result, it seems that parts in that unit seem to wear out faster than the rest of the movement.

Having said that though, there really shouldn’t be any significant difference in wear between the two if both are serviced at regular intervals. Which should be every three to five years if the watch is worn every day, depending on how hard one is on their watches.

Personally, I am amazed that ETA can produce such a thin movement as the 2892-A2 and not only make it as sturdy and as reliable as their thicker movements, but as I mentioned earlier if there is a more accurate or reliable movement than this, I haven’t seen it.

Tying it All Together from My Soapbox

While I’m on my soap box, there are a few other related issues which I feel need to be addressed.

First of all – the basic issue of what makes an accurate movement. Repeating what I said before, I believe that any good movement is an excellent execution of a design whose compromises, while as few as possible, have been intelligently chosen. Making any one area outstanding, while neglecting others will result in a flawed movement.

I think that the Patek Philippe Caliber 315 is a perfect example. In its incarnation as Caliber 310 they had a movement that was very thin, had a large central oscillating weight, was very accurate and reliable, but had undue wear in its automatic winding system. Instead of just refining and fixing up what was wrong, namely choosing better reduction ratios etc better suited to the higher torque 28,800 beat movement, they completely redesigned it and simultaneously reduced the stress on it by reducing the beat to 21,600. So now they have a movement that is outstanding in its efficiency of the automatic winding, and only mediocre as far as accuracy is concerned – mediocre for PP that is.

In my experience, the PP Cal. 315 is not as accurate as its older cousin, the PP Cal. 240 and significantly less accurate than its predecessor, the PP Cal. 310. Don’t get me wrong, it’s still a great movement, and is capable of reasonably good timing, but in their quest to improve one area – automatic winding wear and efficiency – they had significant losses in another area – the important area of accuracy. In my opinion, the change in accuracy is due mostly to the reduced beat and the gyromax balance, as the basic going train is virtually unchanged. Specifically, the great wheel, third wheel and pallet fork are interchangeable between the two. So, all in all, in my book, the compromises for this movement could have been more intelligently chosen.

A second example of the above is Rolex’s insistence on sticking with the archaic oscillating axel for the sake of winding efficiency, instead of switching over to ball bearing races like virtually everyone else. Including them for their new Cal. 4130 chrono movement. The results are movements that are very accurate, but suffer undue wear due to the oscillating weight scraping up against the movement bridges every time the watch suffers a slight shock. Not to mention, this creates many broken axels, and, although less common, broken axel jewels for the same reason.

Which brings me back to the issue of accuracy. What exactly is my (and most watchmakers) definition of an accurate movement. Easy, one that is consistently easy to get good amplitude and good timing from, and doesn’t have undue loss of balance amplitude from the horizontal to the vertical positions. COSC quality timing can be achieved by most good quality movements, but ones that are inherently accurate don’t require any special skills or hours of delicate tweaking to achieve that goal. If one achieves outstanding timing from a movement after many hours of tweaking, to me that’s not a reflection of how accurate the movement is, but rather a reflection of how talented the adjuster is. As has been pointed out before, almost any movement can achieve outstanding timing if enough time, effort and talent are spent on it by one who is an expert in that area.

On the other hand, if most watchmakers can achieve outstanding timing with a minimum of time and adjustments, that’s a reflection of the inherent accuracy of the movement. Of course there’ll be those that disagree with me. This is just the way that I see these things.

The Proud, the Few, the Accurate

So which movements meet my criteria? This short list of outstanding movements should all easily achieve a daily consistency of five seconds or better on the wrist. Those people wanting better accuracy than that, will be much happier with a thermo or radio controlled quartz watch.

Of those currently in production, I’d list the ETA 2892-A2, ETA 2824/2, ETA 7750, JLC 889/2 (and its variations by other brands), JLC 960, all of the current Rolex calibers, Longines 990 (Lemania 8815), PP 215, PP 240, Zenith 400. This is a very small list, I know, mainly because there are many fine movements with which I have very little, or no experience at all. L.U.C. Parmigiani etc.

Some movements that I’ve found delivered excellent timing, but I’m reluctant to put them into the above category because I’ve only serviced/timed one or two of them. FP 1180, FP 1150, Lange 901.0, Omega 2500, Zenith 670, GP 3100.

ETA 2892 Flavors

Quite a few people were curious about the fit and finish of the various 2892’s currently on the market. That’s a really difficult question to answer, as some types of finishes are more attractive than others. Also, some give the appearance of a better finish. In reality, its just a finer decoration finished to the same degree, like fine perlage versus heavy stripes.

My experience has been that the ones that have the nicest quality finish are Breitling, Cartier GP/Bulgari 220, Frank Muller 2800 , IWC’s 375XX and the Ulysse Nardin. The Omega 1120 is one small step above the others. Why do I put it slightly ahead? Because it’s the only one that is as nicely finished on the dial side as it is on the working side.

Omega Caliber 1120

All of the above tend to be very well adjusted in terms of fit and timing, excepting the Cartier. Unless, of course, the watch was in a package that was used for football practice by UPS/FEDEX or the USPS on route to your wrist. A small investment in time and effort could easily bring the Cartier up to par. I should also point out that only the Frank Muller and IWC appear to completely lubricated by hand, save for the barrel and mainspring. The others appear as if they have gone through bulk lubrication. Not necessarily a bad thing, but certainly quicker and cheaper.

Omega’s Co-axial

Finally, just a few words about Omega’s co-axial escapement. I don’t have enough words of praise for Omega’s sheer courage, guts, and fortitude in taking on Daniels’ co-axial escapement. This is a project that required not only enormous courage in venturing into the unknown – is there anybody out there that can say with a straight face and 100% honesty that they really understand this design, besides Dr. Daniels himself? – but also a significant investment on their part in order to make and adjust parts to tolerances of unbelievable precision. Yes, there were teething problems in the first batch, but no whining and crying on their part. Instead, they went back to the drawing board, ever tighter tolerances and even greater precision in manufacturing and voila! It finally seems to be delivering what was promised all along: greater long-term stability in amplitude and timing.

Yes, I know that Omega boasted that now service intervals can be dragged out to ten years. I don’t see how, as all the other parts are still subjected to the same stress and wear as a movement without the co-axial escapement. For example, the barrel and mainspring, the automatic winding unit, the great wheel and third wheel, and the dial train all require service.

From what I’ve seen, it definitely seems to deliver long term accuracy and stability. As far as long term wear and tear are concerned, it’s still too soon to tell. But I’m going to put my money where my mouth is, and hopefully buy one for myself in the not-too-distant future; I think it’s that good. And no, I neither work for Omega nor have shares in Swatch or any of their subsidiaries.